My novelette, An Illicit Mercy, is part of a new promotion in January, BAD-@SS WOMEN.

Check out over 115 novels and short stories, available for free.

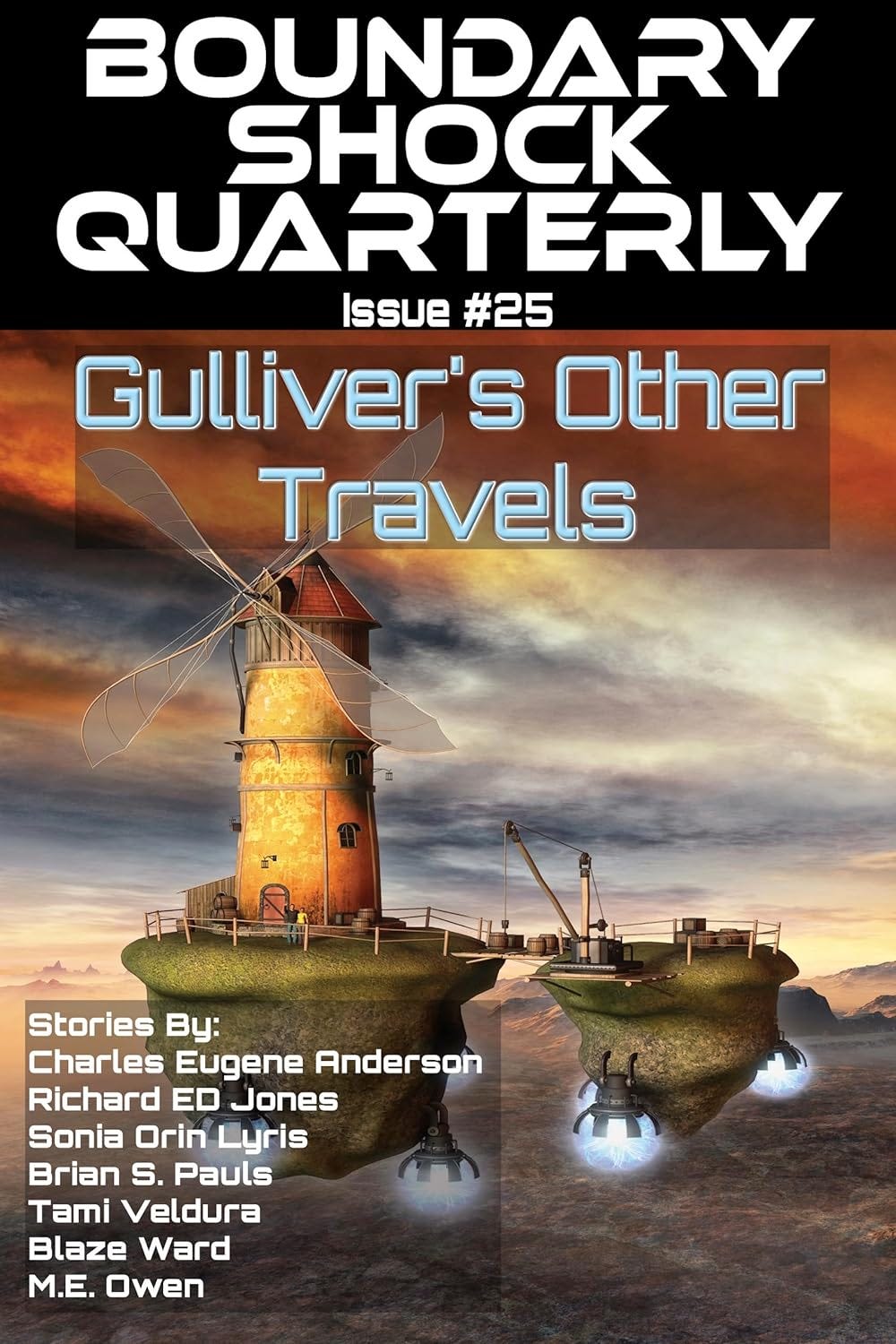

My latest novelette, “In the Country of Free Men,” appears in Boundary Shock Quarterly 25: Gulliver’s Other Travels:

In this thrilling tale, Granuaile Moore, the great-granddaughter of Lemuel Gulliver, travels to the mysterious Moon. There, she gets caught up in an adventure beyond her wildest dreams.

When her scout flyer is attacked and destroyed, Moore finds herself at the mercy of the cruel ruler known as the Drummer. Imprisoned in his decaying palace, she befriends Tichollo, a young servant boy, and hatches a desperate plan to escape back to Earth.

Pursued by the Drummer’s soldiers, the two race across a bizarre lunar landscape in a bid for freedom. They must reunite with the island-ship Lemuel II, if it's still there!

Moore’s quest to explore new worlds has led her into grave danger. But with courage and cleverness, she might live to sail the skies once more.

Deep in the heart of Texas, at the UOG training base, Kevin Ore's dream of touching the stars becomes a thrilling reality. Yet, beneath the glittering promise of space, shadows stir. Commander Mitchell's probing doubts set the stage for a journey where courage will be tested beyond the limits of gravity.

As Kevin navigates weightless simulations and forms bonds with fellow aspiring astronauts, his encounter with the enigmatic Mary unlocks a Pandora's box of mysteries.

Meanwhile, June Thriller's stellar piloting abilities catapult her into the world of the Syndicate, where clandestine missions and covert alliances blur the line between heroism and treachery. As Syndi 005, she's on a trajectory that promises both danger and destiny.

The Birth by Shane Shepherd unveils a world where the cosmos hides secrets, and choices made today will shape the fate of humanity among the stars. Dive into this tantalizing prelude of The Nexus Series, where dreams, intrigue, and the unknown beckon you to embark on an unforgettable odyssey.

The return of self-styled Nazis to national prominence is now affecting the Substack platform on which I publish, prompting me to write this article about the intersection of science fiction with Nazis, fascism, and other totalitarian or authoritarian ideologies. This is Part 2 of a three-part essay. I released Part 1 last week.

“Whether the mask is labeled fascism, democracy, or dictatorship of the proletariat, our great adversary remains the apparatus—the bureaucracy, the police, the military. Not the one facing us across the frontier of the battle lines, which is not so much our enemy as our brothers' enemy, but the one that calls itself our protector and makes us its slaves. No matter what the circumstances, the worst betrayal will always be to subordinate ourselves to this apparatus and to trample underfoot, in its service, all human values in ourselves and in others.”

―Simone Weil, “Reflections on War”

As we saw in Part 1, science fiction literature has confronted Nazis, fascism, and other forms of totalitarian/authoritarian government. It’s regrettable the responses of the field haven’t always been profiles in courage. Across the totalitarian landscape of the 20th century, some science fiction authors and editors were complicit or silent as often as others stood up for the principles of a free society.

I’m indebted for much of the following to the work on science fiction under totalitarianism published by pulp historian Jess Nevins from 2012 to 2013. For those who are interested, I recommend reading all four of his Gizmodo articles, linked in the relevant sections below.

The Soviet Union

Soviet censors tried, with mixed results, to tame the spirit of science fiction and make it serve the goals of the state. Some authors and editors produced work free, to a large-extent, of political meddling. Others collaborated.

In 1922, Alexei Tolstoi published Aelita, in Nevin’s words, “…a planetary romance in which Los, a Soviet scientist and inventor, travels to Mars and, with the help of a Red Army officer, overthrows the fascist civilization there and institutes a Communist paradise.”

Some writers (not just science fiction writers) left the Soviet Union. Yevgeny Zamyatin published his seminal dystopian novel, We, outside the Soviet Union in 1924. He then moved to France in 1931. But We wouldn’t appear in the Soviet Union until 1988, over fifty years after Zamyatin’s death, and a mere three years before that nation’s collapse.

Imperial Japan

Ideological science fiction in pre-democratic Japan possessed a strong anti-Western bent. The field created a “White Peril” trope to compliment the Yellow Peril stories popular in the West. This began as the idea of Japan leading the rest of Asia in a confrontation with Western imperialism. But following the 1931 Japanese invasion of Manchuria, it took on the more sinister tone of Japan fighting Western obstacles to its own Asian imperialism.

Hirata Shinsaku’s New Battleship Takachiho typifies the White Perial story: “…a Japanese naval expedition to the Arctic in search of a secret route into the Atlantic is suddenly attacked and sunk by the forces of the countries ‘A’ and ‘B,’ implicitly America and Britain. (The survivors of the attack are saved by a flying battleship).”

Nazi Germany

It seems the best science fiction authors and editors could manage, following Hitler’s rise to power in January of 1933, especially from 1936 until the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, was silence regarding fascist values. And even silence resulted in the cancellation of popular magazines and their replacement with doctrinaire substitutes.

Others collaborated with the Nazi censors to the extent of creating ideological fables. The Ases novel series by Edmund Kiss, for example, is an Aryan origin story. The white-skinned “master race” rules Atlantis, served by their brown-skinned slaves. Following the destruction of their homeland, the Ases become the ancestors of—you guessed it!—the German people.

Francoist Spain

Because of censorship laws in Spain, science fiction during Franco’s rule said nothing about politics. Unlike Nazi Germany, Spain had no strong wing of authors and editors carrying water for the regime—but neither did writers oppose it openly.

Spain produced much derivative science fiction during this time, like Vallve Lopez's Hercules, a Basque version of Doc Savage.

The Peoples Republic of China

At first, science fiction in China followed the Soviet model. Since then, the genre has gone in-and-out of fashion. Banned entirely under Mao, it experienced a resurgence when Deng Xiaoping came to power in 1978.

The situation of Chinese science fiction authors remains complex. Han Song, for instance, publishes science fiction containing certain political ideas outside the country. But he remains popular within China for less sensitive work. One of his best known stories is 2066: Red Star Over America, which predicted “…a large-scale terrorist attack on the World Trade Center…” prior to 9-11.

The Chinese government has often sought to use science fiction to promote its ideology, a practice which continues today with Wandering Earth II, a sequel to the movie based on Cixin Liu’s novella, “The Wandering Earth.”

The Church of Scientology

No discussion of science fiction’s complicity with totalitarian worldviews would be complete without mentioning The Church of Scientology, an outgrowth of Dianetics.

Elements of the science fiction community supported the movement from the beginning, marked by the publication of L. Ron Hubbard’s 1950 book, Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health. John W. Campbell, Jr., the editor of Astounding Science Fiction, launched Dianetics in the pages of his magazine. He even helped Hubbard secure a publisher. Popular science fiction writer A. E. van Vogt promoted Dianetics for a decade, from 1951 to 1961, interrupting his writing career to do so.

Following a split with some of his followers in 1952, Hubbard formed The Church of Scientology in 1953.

Former church members such as Margary Wakefield and Ursula Caberta have described Scientology as totalitarian. Wakefield maps the practices of the church to Robert Lifton’s eight features of “totalism” (totalitarian methodologies usable by non-government groups):

Milieu Control

Mystical Manipulation

Demand for Purity

Confession

Sacred Science

Loading the Language

Doctrine over person

Dispensing of existence

While Scientology is not the first totalitarian religious movement, it’s the only one I know of which came into existence through the explicit actions of the science fiction community. It’s also the only religion with a corporation owning a competition to find and develop new science fiction authors. The Writers and Illustrators of the Future contest began in 1985 and is still active today. All rights to the contest are owned by The Church of Spiritual Technology, a “Scientology-related entity”.

But what does all this have to do with free speech in a liberal democracy like the United States? Next week I’ll take a look at what science fiction has to say about limiting one of our most cherished civil rights.

Questions or comments? Please share your thoughts!