My novelette, An Illicit Mercy, is part of a new February/March promotion, Clean Sci-fi & Fantasy.

Check out over 100 novels, excerpts, and short stories, available for free.

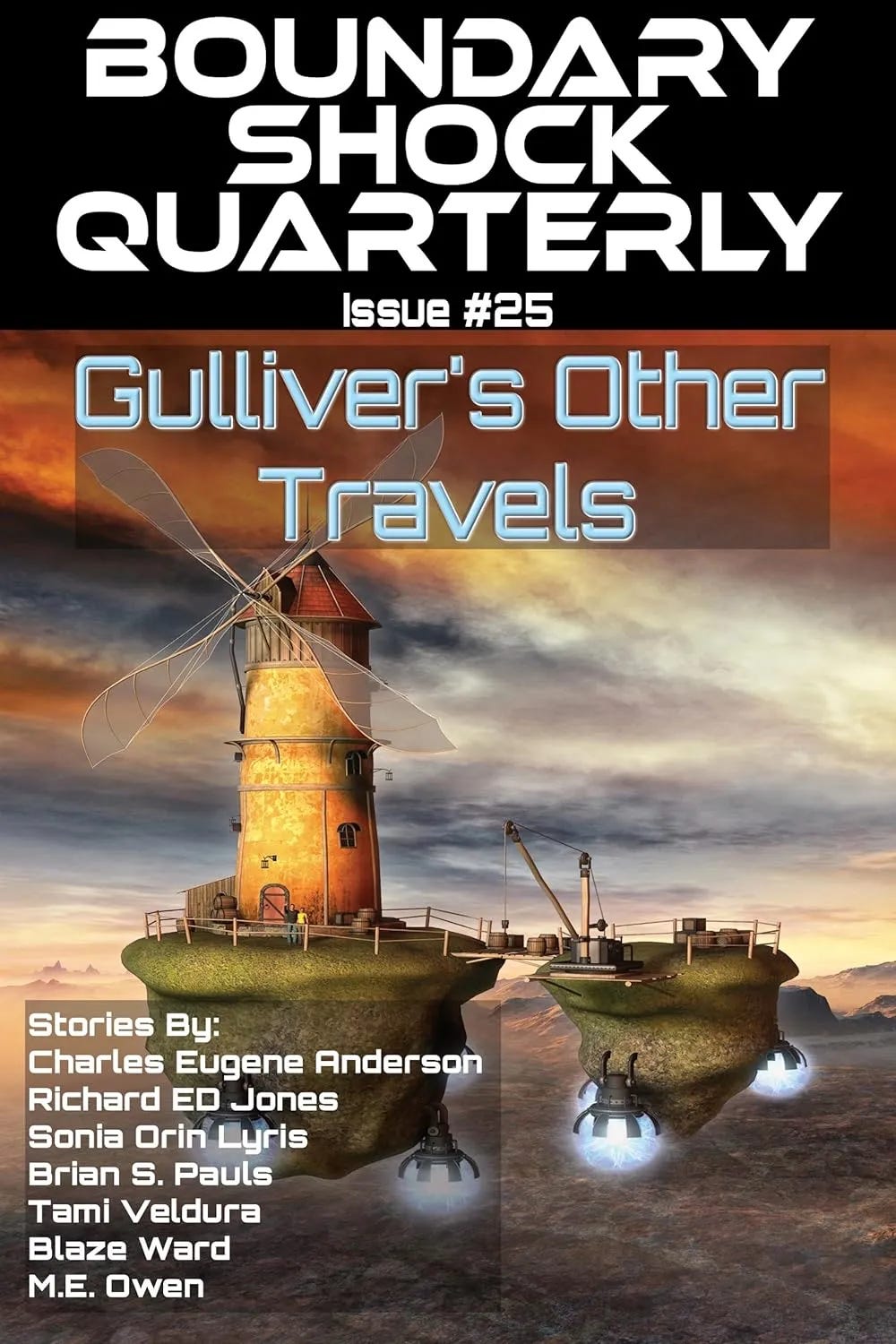

My latest novelette, “In the Country of Free Men,” appears in Boundary Shock Quarterly 25: Gulliver’s Other Travels:

In this thrilling tale, Granuaile Moore, the great-granddaughter of Lemuel Gulliver, travels to the mysterious Moon. There, she gets caught up in an adventure beyond her wildest dreams.

When her scout flyer is attacked and destroyed, Moore finds herself at the mercy of the cruel ruler known as the Drummer. Imprisoned in his decaying palace, she befriends Tichollo, a young servant boy, and hatches a desperate plan to escape back to Earth.

Pursued by the Drummer’s soldiers, the two race across a bizarre lunar landscape in a bid for freedom. They must reunite with the island-ship Lemuel II, if it's still there!

Moore’s quest to explore new worlds has led her into grave danger. But with courage and cleverness, she might live to sail the skies once more.

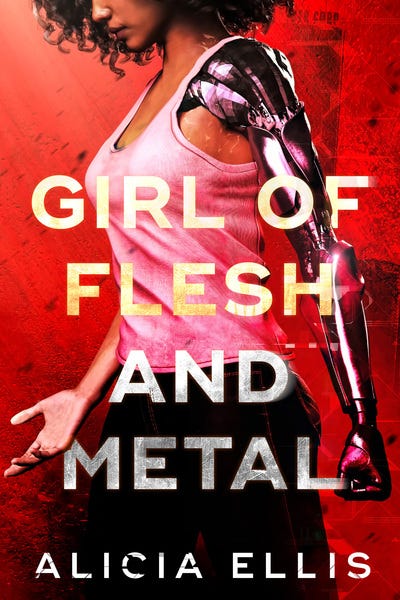

Get your free copy of Girl of Flesh and Metal, by Alicia Ellis, the first novel in the Flesh and Metal trilogy.

A devastating accident. An artificially intelligent prosthetic that makes her sleepwalk… A series of murders.

Lena hates her parents’ tech company. The world worships each cutting-edge CyberCorp release, but Lena has her doubts. Machines that think for themselves? She doesn’t trust them… So when a car accident lands her with the company’s first cybernetic arm, she’s pissed.

A glitch in the arm’s artificial intelligence makes her sleepwalk. Meanwhile, children of CyberCorp employees start dying in their beds, and thanks to her unwanted nighttime strolls, Lena has no alibi.

Is she a target? A suspect? Lena literally can't sleep at night until she proves her innocence—or her guilt.

Marissa Meyer’s Cinder meets Netflix’s Black Mirror in this YA sci-fi murder mystery with a twisty ending you won't forget.

Don't miss the first self-published book ever to make the American Library Association’s LITA Excellence in Children’s and Young Adult Science Fiction Notable Lists.

Club Codex is reading and discussing the Prometheus Award-winning novel “Cloud-Castles” by Dave Freer through March 16. Please join us!

The return of self-styled Nazis to national prominence is now affecting the Substack platform on which I publish, prompting me to write this article about the intersection of science fiction with Nazis, fascism, and other totalitarian or authoritarian ideologies. This is Part 3 of a three-part essay. I released Part 1 and Part 2 in January.

”The exercise of imagination is dangerous to those who profit from the way things are because it has the power to show that the way things are is not permanent, not universal, not necessary.”

—Ursula K. Le Guin, “A War Without End”

As we saw in Part 1 and Part 2, science fiction in recent history has both resisted and enabled fascist regimes and other forms of totalitarianism. In the final installment, we will discuss science fiction in the specific context of free speech. How should sf authors and readers tackle the challenges of an interconnected society dependent on rational decisions made by each individual?

I ended Part 2 by saying this last essay, directly addressing free speech, would be available the next week. Here it is, over six weeks later.

The cause of the delay was to make sure I was accurately speaking my mind. Prior to the 2016 presidential election and the COVID-19 pandemic, I was fond of saying free speech was an American absolute. The years following the 2016 election shocked me with how many Americans were willing to accept blatant and obvious falsehoods which accorded with their political or personal biases. News reports made it obvious how much harm could result from such faulty thinking. This shook my confidence in the decision-making abilities of the American public. Perhaps our commitment to free speech shouldn’t be as expansive as I once thought.

Faced with the challenge of addressing this topic, I had to sort out what I now believed. To do this, I read. Primarily, at the prompting of Christopher Hitchens in his University of Toronto debate appearance, I read Mill’s “On Liberty” and Milton’s “Areopagitica.” I also studied a number of articles on both sides of the issue.

If you look hard enough, you may find social media posts from me over the past decade supporting my conclusions below, and posts contradicting those conclusions. I’m OK with that. I’ve no desire to be constrained by Emerson’s “hobgoblin”—a foolish consistency.

In the classic 1953 science fiction novel Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury, all books are banned. State enforcers known as “firemen” track down surviving volumes and burn them along with the houses in which they’ve been hidden. If the owners of the houses refuse to leave, the firemen burn them too.

Government censorship is the primary theme of Fahrenheit 451. Bradbury wrote the novel in the midst of the McCarthy era, and harbored a fear of possible book burnings in the United States, such as those carried out in Nazi Germany.

In Part 1, we reviewed how authoritarian and totalitarian regimes are a frequent topic in serious science fiction. In addition to Bradbury’s parable, works such as Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale,” Octavia Butler’s Parable duology, Ursula K. Le Guin’s “The Diary of the Rose,” and Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle In Time include examples. Oppressive governments are a clear theme in sf.

Free speech and the Internet

But we can suppress the spread of ideas by using social pressure, rather than government. Does the source of the suppression change its morality?

The Substack platform on which I publish this newsletter has courted controversy by allowing publishers to share white supremacist, anti-Semitic, and fascist views in their newsletters. Some of these newsletters accept paid subscribers, which means Substack is collecting revenue from the dissemination of such odious perspectives. As a result, some are taking the company to task for not using the social pressure available to it—control of its own web-publishing platform—to limit the spread of hateful ideas.

Substack has joined what may be the most important argument of the early 21st century: free speech vs. the Internet. This is a very science fictional concern. Many sf stories predicted today’s Internet, including Orson Scott Card’s Enders Game, which we discussed in Part 1.

Like most other Americans, I have little desire to live in the sort of dystopia Bradbury depicts. Or anything like its real-world analogs, Nazi Germany and Stalinist Russia.

In the United States, much of the contemporary discussion about freedom of speech revolves around the First Amendment to our Constitution, and whether certain restrictions would be censorship. Proponents of restrictions often point out censorship is the action of governments. Private companies, like those owning social media, aren’t bound by the same rules. They don’t have to follow the First Amendment.

They don’t have to. But maybe they should. It depends on the sort of society in which we want to live.

Freedom of thought

The United States is an experiment of the Enlightenment. The doctrine of natural rights which that movement celebrated is enshrined in our founding documents. Chief among these rights, as specified in the First Amendment, are the freedom of religion, speech, and the press. These three are grouped together for a reason. Each is a manifestation of a more fundamental freedom, not spelled out, but essential to the spirit of the First Amendment. We are each ensured the inviolate freedom of thought.

Recognition of this freedom, and the related liberties to worship (or not) as we choose, to speak without restraint, and to publish as we are able, goes back at least as far as John Milton. In 1644, the poet penned “Areopagitica,” an argument against the censorship of books and other publications in England. In his polemic, Milton defends the freedom to both read and publish as follows:

“…books are not absolutely dead things, but do contain a potency of life in them to be as active as that soul was whose progeny they are; nay, they do preserve as in a vial the purest efficacy and extraction of that living intellect that bred them.”1

Likewise, Milton’s countryman, John Stuart Mill, in his 1859 treatise “On Liberty,” enumerates “…the liberty of thought…”2 as first among the domains comprising “the region of human liberty.”3 Furthermore, he includes “the liberty of expressing and publishing opinions”4 as an inherent part of the liberty of thought.

Restriction by social pressure

It’s true the U.S. Constitution and its Bill of Rights apply primarily to the federal and state governments. But they also define our highest ideals as a country and a people. We prevent governments from abrogating the freedom of speech not because government is bad, but because freedom is good. Would we be satisfied living in a society where this prerogative is universally respected by government, but universally obstructed by everyone else? What if the owner of your favorite coffee shop forbid you and your friends from talking about politics or religion while on the premises? What if it happened at every coffee shop in town? In every town in your state? Few of us would consider this the hallmark of a free society.

Government isn’t the only check on freedom. Society itself can become a fearful oppressor, enforcing the prejudices of the majority, but encoding them in customs rather than laws.

Mill addresses this in On Liberty, via the concept of the “tyranny of the majority”:

“Like other tyrannies, the tyranny of the majority was at first, and is still vulgarly, held in dread, chiefly as operating through the acts of public authorities. But reflecting persons perceived that when society is itself the tyrant—society collectively, over the separate individuals who compose it—its means of tyrannizing are not restricted to the acts which it may do by the hands of its political functionaries. Society can and does execute its own mandates: and if it issues wrong mandates instead of right, or any mandates at all in things in which it ought not to meddle, it practices a social tyranny more formidable than many kinds of political oppression.”5

I want to live in a society which embodies the principles found in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. I want individuals and organizations to respect my freedom to think, worship, speak, and publish because they are my natural rights, because others value these principles as much as I do. I want my fellow Americans to refrain from infringing on these rights because to do otherwise would be anathema to them, not because the law tells them they must refrain.

This view of liberty is much more expansive than that which simply seeks to restrict the powers of government. It seeks a society where all can flourish through mutual good will, as opposed to one where we must continue to be vigilant against all rivals except our government.

The perfect realization of such a society is impossible, but I can do my part by working for it within my own sphere of influence—online and offline.

Irrational hate

“But,” some may object, “we don’t live in a society of ‘mutual good will.’ There are those who use their freedom to the detriment of others—by saying and publishing lies, insults, and hatred. Society must impose constraints when government will not.”

This appears to be the position of science fiction author Annalee Newitz in her 2022 New Scientist article “Twitter and the dangers of the U.S. myth of free speech”:

“It turns out that information overload is just as toxic to democracy as censorship is. We need to chuck out the US myth that bad speech can be ‘cured’ with more speech. Without moderation, ground rules for debate, and thoughtful regulation in our digital public squares, it is impossible for us to reach agreement on anything.”

Newitz’s full argument is worth reading. You can find it linked above, or you can listen to Episode 135, “The Myth of Free Speech,” on her podcast “our opinions are correct,” with fellow sf author Charlie Jane Anders.

In her article “Hateful Fictions”, novelist Siri Hustvedt takes a similar position, engaging Mill directly. Both recognize a valid “harm” exception to free speech. But Mill defines this exception narrowly, as “…perceptible hurt to any assignable individual except [the speaker]…6” He excludes “…the merely contingent…injury which a person causes to society…”7 Hustvedt goes further, contending “racist speech” can cause “…possible physiological harm…” resulting from the “…physical manifestations of institutional racism.” Curing such an ill would expand the justification for speech restrictions far beyond “…hurt to any assignable individual…”

Newitz’s and Hustvedt’s objections arise from good intentions. They are attempts to protect those most at-risk in our society. I agree we should challenge horrid speech and publications whenever they appear. People of good will should defend those who may not have the platforms or voices to defend themselves. But after careful consideration, I don’t agree we should suppress such speech and publications by either law or custom.

Who decides?

Why? Because when Newitz and others advocate for moderation to set the ground rules for debate, they appear to assume such moderation will be governed by the tolerant society they prefer, not by its opposite.

This is the conundrum of restricting speech: who gets to decide the restrictions? Who moderates? Who sets the ground rules?

In 2006, author and provocateur Christopher Hitchens participated in a now famous debate about free speech at the University of Toronto. In his presentation, he points out the weakness in arguments advocating restrictions on speech. Referencing Milton’s Areopagitica, Mill’s On Liberty, and the introduction to Thomas Paine’s The Age of Reason, Hitchens maintains the argument boils down to this—who decides which speech will be restricted?

Perhaps you would prefer the government or society to restrict my speech (maybe this very article!) But what if the shoe is on the other foot? Would you be equally willing to allow the government or society to restrict your speech, based on my preferences?

I believe the answer for most Americans is “no.” This is where the argument for restricting speech falls apart.

We can see this playing out before our eyes right now. Dissatisfied with the direction social media moderation has taken since the 2016 presidential election, Florida and Texas have enacted laws interfering with these practices. The United States Supreme Court heard the case last Monday.

The Court is likely to strike down these laws on First Amendment grounds. This doesn’t mean these states won’t try again, by passing different laws—largely because they dislike the effects of the moderation. If the sites moderated themselves differently, focusing on a different set of opinions, other states might be making similar laws.

The bottom line is, toleration must go both ways. When we try silencing others because we disagree with them, we’ve decided we have the right to speak our mind, but they don’t have the right to speak theirs.

The “paradox of tolerance”

A cartoon is making the rounds that purports to disprove this argument as a false equivalence. It references philosopher Karl Popper’s “paradox of tolerance,” as laid out in his work “The Open Society and Its Enemies.”

According to the cartoon, everything must be tolerated except intolerance. Because intolerance does not permit opposing views, it shuts down debate. Eventually, “unlimited tolerance can lead to the extinction of tolerance.” Therefore, the cartoon concludes “…defending tolerance requires to not tolerate the intolerant.”

But the cartoon doesn’t accurately reflect Popper's full argument. In his words:

“…I do not imply, for instance, that we should always suppress the utterance of intolerant philosophies; as long as we can counter them by rational argument and keep them in check by public opinion, suppression would certainly be most unwise. But we should claim the right to suppress them if necessary even by force; for it may easily turn out that they are not prepared to meet us on the level of rational argument, but begin by denouncing all argument, because it is deceptive, and teach them to answer arguments by their use of their fists or pistols. We should therefore claim, in the name of tolerance, the right to not tolerate the intolerant. We should claim that any movement preaching intolerance places itself outside the law, and we should consider incitement to intolerance and persecution as criminal, in the same way as we should consider incitement to murder, or to kidnapping, or to the revival of the slave trade as criminal.”8

As you can see, the citation above contains most elements of the cartoon, except the conclusion that “…defending tolerance requires to not tolerate the intolerant” (emphasis mine.)

When Popper refers to the use of force, he’s talking about government control. It’s obvious he also considers “public opinion” an acceptable “check” on “intolerant philosophies.” But the form of public opinion he advocates isn’t restricting speech. It’s “rational argument,” itself a form of tolerance.

Popper’s criteria for ceasing to tolerate the intolerant include physical violence: “…their use of their fists or their pistols.” This accords with our existing practices in the United States. As law professor Jeffry Rosen, the president and CEO of the non-partisan National Constitution Center, explains, “…the First Amendment generally protects hate speech unless it is intended, and likely, to cause imminent injury.”

But Popper was Austrian and British, not American. His criteria also include a category of speech the banning of which would run afoul of our First Amendment: “incitement to intolerance and persecution.” It’s clear from Rosen’s explanation above that the Constitution generally protects even this type of speech.

Some might consider the expression of such views so foul as to place the speaker outside the bounds of acceptable public discourse.

While I agree with the sentiment, I cannot agree with the argument. The reason is the subjectivity of the terms “intolerance” and “persecution,” and therefore the vague nature of what constitutes incitement to these practices.

Incitement to violence, in its most basic form, is clear. If you are advocating physical harm to anyone, you are clearly inciting violence.

But what are “incitement to intolerance” and “incitement to persecution?” Many Americans would consider preaching anti-Semitism a clear example of both. But what of the anti-Semite who donates a copy of “Mein Kampf” to a public or private library, only to have it rejected because it incites intolerance? Is this criterion objective or subjective? Does everyone have an equal right to claim they are a victim of intolerance or persecution? If not, who decides? If so, how do we keep such criteria from becoming meaningless?

Suppression doesn’t work

We can’t cure hate with content moderation. The most we can do is suppress it. This might allow us to stop thinking about it for a while, but such tactics won’t make it go away. How many racists or fascists have you seen change their minds because of Facebook bans?

Attempts to suppress appalling worldviews may even have the opposite of their intended effect. In her landmark book The Origins of Totalitarianism, philosopher/historian Hannah Arendt contends the isolation and alienation of certain segments of German and Russian society made possible the Nazi and Stalinist regimes of terror.

Out of fear, we may incline toward suppression as the solution to what we see as a corrosive social problem. This was my immediate reaction when I saw lies running wild on the Internet. Perhaps we had let free speech go too far. But I was wrong. Suppression may backfire with catastrophic results. It has failed in the past. We are not immune.

What does work?

Do you know what succeeds? Civil engagement.

I invite you to read the story of one of my heroes, Daryl Davis. He’s a black pianist who has convinced white supremacists to change their ways— at least two hundred of them. He didn’t do this with government power or social pressure. He did it by talking with them and becoming their friend. By accepting them as people, he did what I’m convinced social media moderation has never accomplished and never will. He gave them an argument they would accept to leave their hate behind.

We can’t all be Daryl Davis, but we can all choose engagement rather than insults and alienation in our in-person and online interactions. Vitriol may make us feel better, but it produces few converts.

I agree with Popper and Mill. The best way to confront intolerance is with rational argument. If we use our government or social power to suppress it, attempting to isolate those who hold hateful views, at most we’ll drive it underground.

Rather than chasing hate away to hide in dark holes on the Internet, I prefer to have it out where I can see it. That way, I’ll know what I’m facing. And I’ll have the opportunity to confront it with civility, compassion, love, and reason.

And those who hate deserve this opportunity to speak publicly. Not because of what they believe, but because of who they are—human beings with natural rights. The most basic of these is the freedom to think, and to share what they think with others, even on the Internet.

I won’t condemn social media platforms that take this freedom seriously. I also won’t condemn them for charging for their services. Their services aren’t the problem, any more than Gmail is the problem with a fascist sending out email blasts.

But I have some advice.

Substack, please consider donating your profits from those hateful accounts to organizations dedicated to healing the hate they spread. You can protect the account holders’ freedom to publish and do some good with your cut of the revenue they generate. Win/win.

I’m a science fiction writer. At its best, science fiction literature pushes boundaries. Many sf stories and novels challenge cultural assumptions and mores. A number have been banned. I don’t want to see this happen in my country or my world, to my stories or anyone else’s. I want to see an end to the suppression (by whatever means) of the spoken and written word. Because I ask this for myself, I must accord the same to everyone else. Let’s abandon the temptation to naked power, and take up instead the power of words. They are mightier still.

Questions or comments? Please share your thoughts!

1 Milton, John, “Areopagitica,” 2014, Penguin Group, p. 101

2 Mill, John Stuart, “Essential Works of John Stuart Mill,” 1961, Bantam Books Inc., p. 265

3 Mill, John Stuart, “Essential Works of John Stuart Mill,” 1961, Bantam Books Inc., p. 265

4 Mill, John Stuart, “Essential Works of John Stuart Mill,” 1961, Bantam Books Inc., p. 265

5 Mill, John Stuart, “Essential Works of John Stuart Mill,” 1961, Bantam Books Inc., p. 265

6 Mill, John Stuart, “Essential Works of John Stuart Mill,” 1961, Bantam Books Inc., p. 329

7 Mill, John Stuart, “Essential Works of John Stuart Mill,” 1961, Bantam Books Inc., p. 329

8 Karl Popper, The Open Society and Its Enemies, ed. Alan Ryan (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013), p. 513

Science fiction, Nazis, and free speech (Part 3)