My novelette, An Illicit Mercy, is part of a new promotion in January and February: Moral Dilemmas in Fantasy & Science Fiction.

Over 40 short stories, novels, samples and excerpts, available at no cost.

"When the skies turned red and the stars fell, humanity's fight for survival began."

Get your FREE copy of Defending Earth by C. S. Hawk.

When a horde of slimy extraterrestrial creatures arrives on Earth with an insatiable appetite for destruction, three unlikely heroes step up to defend our planet.

As they navigate the dangerous terrain of a world under siege, they face countless obstacles and setbacks but never lose their sense of humor. After all, when the fate of humanity is on the line, there's nothing like a good joke to keep your spirits up.

Will they succeed in repelling the alien invasion and saving the planet? Only time will tell.

In his review of Algis Budrys’ 1960 Hugo-nominated novel Rogue Moon, James Blish calls its characters “as various a pack of gravely deteriorated psychotics as has ever graced an asylum.”1

Ned Beauman might have writtenVenomous Lumpsucker with this statement pinned to the wall above his monitor. He tells the story of broken, deranged people living in a broken, deranged world. Climate change is breaking their world and driving it mad. The characters’ collective guilt for this existential crime is doing the same to them.

Venomous Lumpsucker would be depressing if Beauman wasn’t so deft with his satire. The fate of the world he’s created makes me want to cry, because it’s the fate of the world we’re creating right now. But the human foibles Beauman throws into sharp relief are so familiar, I ended up wanting to laugh—at myself and everyone else.

The novel tells the story of Mark Halyard, a near-future business executive with a problem. He’s about to get caught short-selling “extinction credits” he doesn’t own.

Extinction credits are financial instruments like carbon credits. Each gives the owner the legal right to drive one species into extinction, and they’re traded on an exchange. Halyard steals his company’s credits and sells them on the exchange. He plans to buy them back when the price drops, so he can replace them before his company realizes they’re gone.

Halyard’s plan revolves around a coming regulatory change that will cause the price of extinction credits to crash. He sees selling short as a can't-lose proposition. But when the unthinkable happens, the value of the credits instead skyrockets. Halyard is left holding the bag for the now exorbitant price of the credits he stole.

He hopes the company won’t need their credits—meaning they won’t cause the extinction of any species—before he can devise some way out of his predicament. But this hope is dashed when Halyard learns automated undersea mining equipment owned by the company has plowed through the last known habitat of an endangered species of fish—the venomous lumpsucker. Now the company will want to redeem their credits to pay for their mistake. Unless Halyard can find a surviving population of lumpsuckers to stave of his own financial and legal Armageddon.

This leads him to Karin Resaint, perhaps the world’s foremost living expert on venomous lumpsuckers. Together, they set off across the globe in search of survivors—she to save them, and he to save himself. Along they way, I learned about what a world facing an “extinction crisis” has done to them both, how it has driven each of them crazy in their own way. And they meet a host of characters who are just as crazy, or crazier. These include a former government minister from a country known as the “Hermit Kingdom” (which isn’t where you may think) and an entrepreneur on a city floating in the ocean who has dedicated a project to churning out clouds of flies and setting them free.

Venomous Lumpsucker is a sad, humorous, and philosophical book about evolution, ecological peril, extinction, animal consciousness, capitalism, and moral culpability. It’s filled with thoughtful observations from flawed characters, such as when Halyard sums up the worldwide destruction of the “biobanks” which were supposed to save the data profiles of extinct species so humanity could someday resurrect them.

“We had pawned those animals intending to buy them back one day when things were a bit less stretched, and now the pawn shop had burned to the ground with all the animals inside.”2

Or Resaint’s cynical take on the same topic.

“‘…I never really gave a shit about the biobanks. I never believed we were going to bring any of those species back, except maybe a few of the cuddly ones. It was always just an empty ritual.’”3

Beauman is at his best when he’s talking about both the brutality and the beauty of evolution.

On the one hand, it’s savage and without pity, “red in tooth and claw,” in Tennyson’s words.

“Evolution was a monstrous maker, a blind headless thing inching along in no particular direction, the whole disaster fueled by spilled blood and wasted effort, Amazon rivers of both.”4

On the other hand, evolution is an ingenious inventor, devising solutions, through time and chance (and plenty of death), to puzzles science has yet to master.

“…every feature of every animal is a solution to a technical problem. Examining an animal mind is like examining a missile guidance system or weather-predicting computer designed in some old totalitarian state: it’s primitive, janky, hobbled by extraneous constraints, and yet at the same time it is the most resourceful and inventive technology you have ever seen, still more advanced in certain esoteric ways than anything that has come since.”5

The core question with which Beauman and his characters struggle isn’t the fate of humanity (that’s pretty much considered a lost cause, at least to those who give it any thought at all) but whether or not the destruction of non-sentient species is a tragedy in itself, regardless of the effect it may have on humans.

One side of the argument says that if an extinction event doesn’t impact a thinking organism, it can’t be wrong.

Beauman beautifully captures the other side in a thought experiment Resaint uses to challenge Halyard.

“…imagine a planet in some remote galaxy—a lush, seething, glittering planet covered with stratospheric waterfalls, great land-sponges bouncing through the valleys, corals budding in perfect niveous hexagons, humming lichens glued to pink crystals, prismatic jellyfish breaching from the rivers, titanic lilies relying on tornadoes to spread their pollen—a planet full of complex, interconnected life but devoid of consciousness. ‘Are you telling me that, if an asteroid smashed into this planet and reduced every inch of its surface to dust, nothing would be lost? Because nobody in particular would miss it?“6

If Beauman makes a mistake inVenomous Lumpsucker, it’s by going in too many directions at once, trying to tackle too many big themes, introducing too many side characters, each with their own quirks and psychoses. At times, I would have welcomed less breadth and a sharper focus on Resaint and Halyard as they pursue their own off-kilter goals.

But this flaw didn’t keep me from enjoying the novel.Venomous Lumpsucker is a great read for anyone looking for a dark satire of the near future, a melancholy look at the unintended consequences of human nature. It’s the best recent science fiction book I read last year.

Questions or comments? Please share your thoughts!

In the second half of January, I’m reading Adrian Tchaikovsky’s Children of Memory, the third book in his Hugo-Award winning Children of Time trilogy. I’m sharing my thoughts on Club Codex, where any Cosmic Codex subscriber can follow along, comment, or ask questions.

From this week’s post:

“In this series, Tchaikovsky is establishing himself as a master of the non-linear narrative in science fiction.”

Click below to participate:

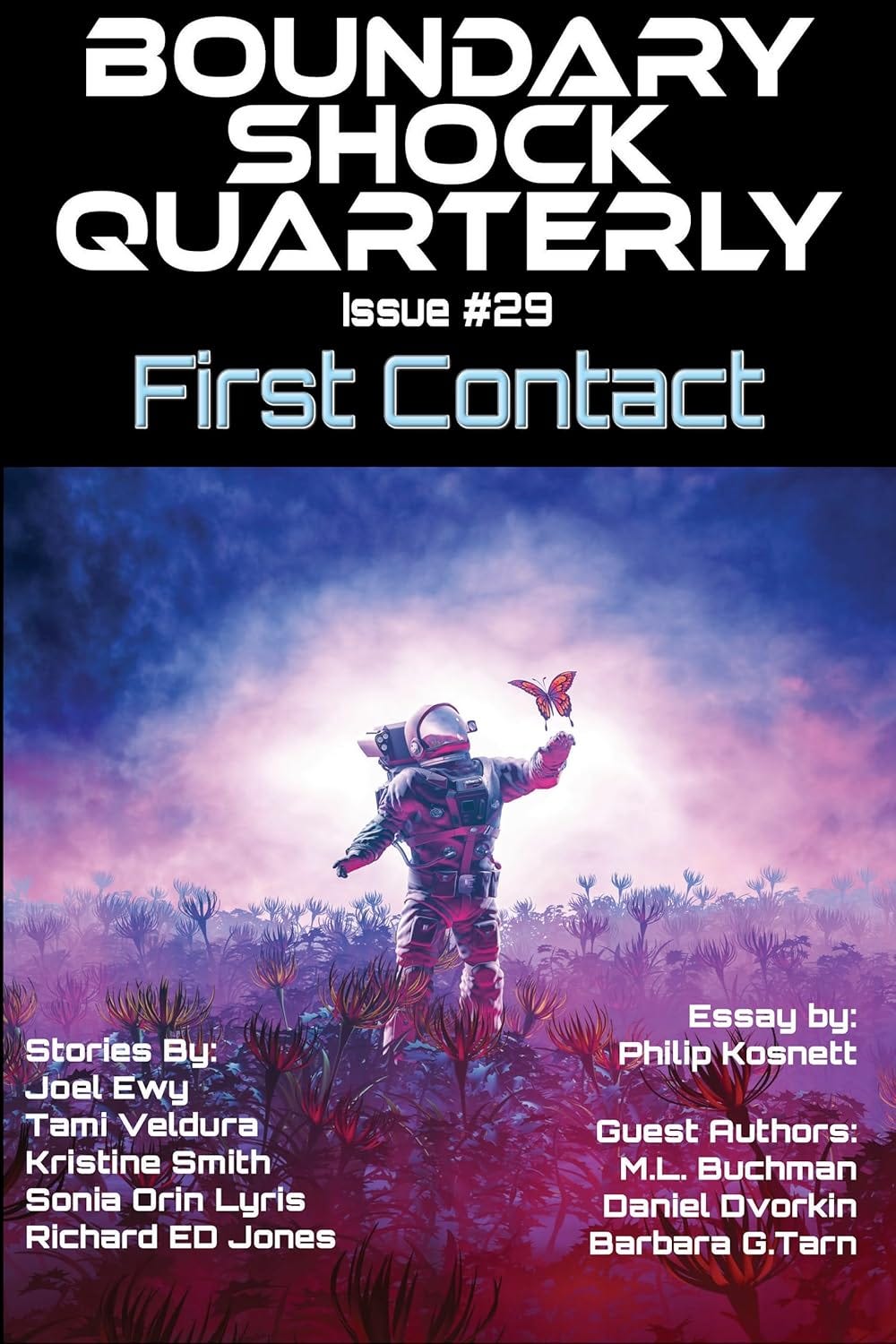

My latest novelette, “Fire From Heaven,” now appears in Boundary Shock Quarterly 29: First Contact.

In the shadows of an alien world, terror awaits. On the radiation-blasted planet Janus, a team of explorers descends into Abbadon—an ancient mountain facility hiding unimaginable secrets. As they navigate bizarre chambers filled with cryptic carvings, they unleash a nightmare. But the true horror lies not in the alien ruins, but in the chilling implications of the team’s discovery.

Fire From Heaven is the sequel to my previous novelette, “Nasty, Brutish, and Short.”

Blish, James. “More Issues at Hand,” Advent:Publishers. 1970. p. 68

Beauman, Ned. “Venemous Lumpsucker,” Soho Press, Inc. 2022. p. 62

Ibid. p. 73

Ibid. p. 112-3

Ibid. p. 45-6

Ibid. p. 185