Launch Failures

What does sf teach us about dealing with mistakes?

My novelette, An Illicit Mercy, is part of a new promotion in March and April, Page Turner Freebies.

Check out nearly 65 books available for free.

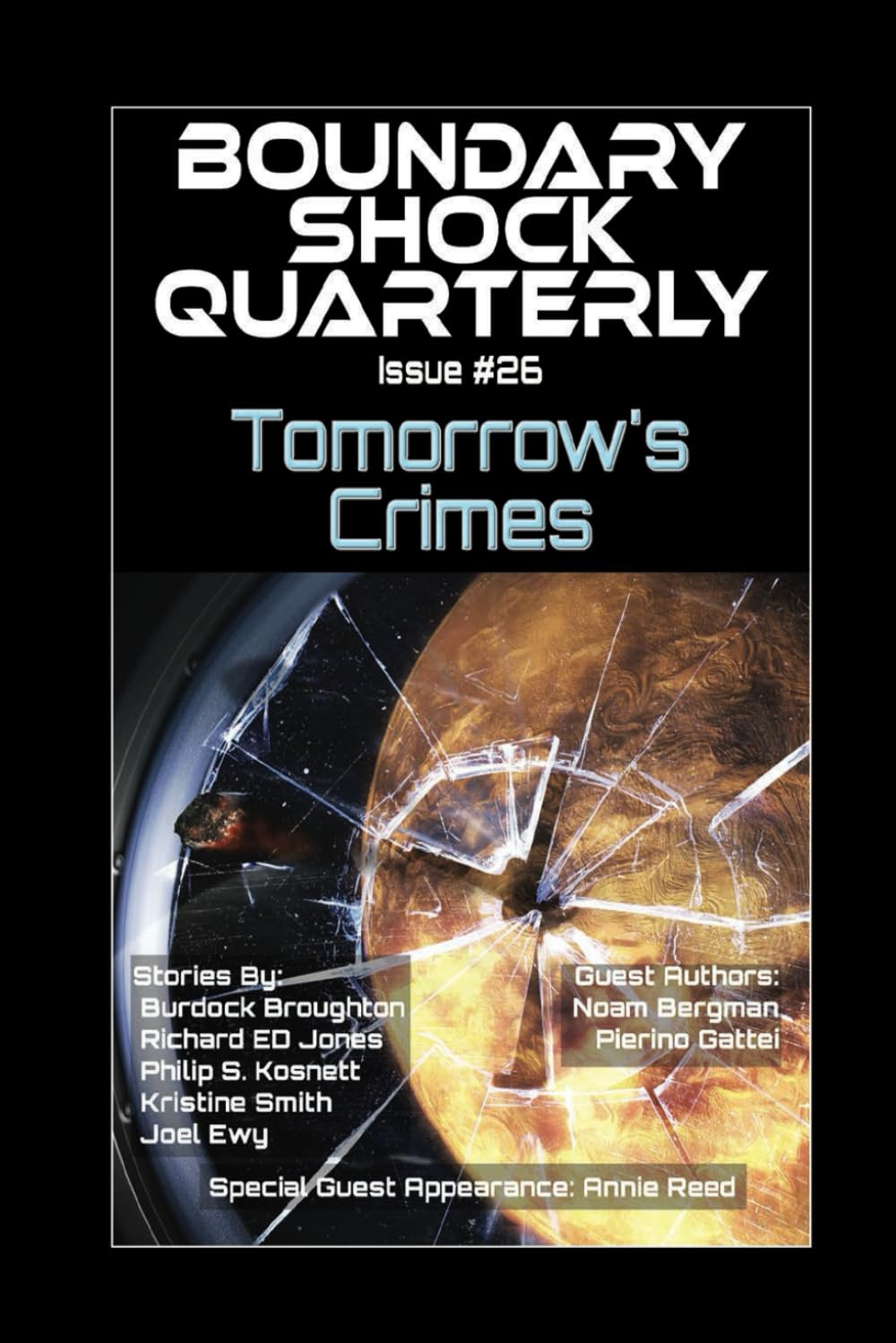

My latest novelette, “Long Night On the Endless City,” appears in Boundary Shock Quarterly 26: Tomorrow’s Crimes:

On the vast ring habitat Ouroboros, Jel and her synthetic companion Marcus search for Arja, the third member of their triad. This quest leads them to a cryptic technology cult with questionable motives. When they suffer a vicious attack, Marcus and Jel join forces with one of Ouroboros’ most renowned computer and robotics experts to get to the bottom of the mystery.

This thought-provoking sf tale explores artificial intelligence, religion, and the ties that bind families together in a fast-paced story full of action, intrigue, and heart.

Five years before Bad Bishop...

Get your FREE ebook copy of First Board!

or get it in paperback.

Five years before the events of “Bad Bishop,” Commander Jerald Norim serves as the XO and second to the Captain of the CSS “Intrepid.”

Estranged from his wife, Jerald must wrestle with the weight of duty as he is thrust into leadership.

This story is meant to shed light on his character, both his strengths and his flaws, and should serve as a solid introduction to the Scions of Oth series.

This is how Jerald became the Bad Bishop.

“…humans hardly ever learn from the experience of others. They learn—when they do, which isn’t often—on their own, the hard way.”

—the character of Lazarus Long in Robert A. Heinlein’s Time Enough for Love

Everyone makes mistakes. This doesn’t make it feel any better when you’re the one making them.

As I mentioned last week, my latest novelette, "Long Night on the Endless City,” appears in Boundary Shock Quarterly 26: Tomorrow’s Crimes.

I tend to do most of my reading in the Kindle app on my iPhone. But I like to see my writing in print. And I like to make it easily available for the rest of my family to read—mostly a vain aspiration, I’m afraid.

Still, hope springs eternal. So I always order a print copy of BSQ to keep on the sf shelf in our family library. Last Saturday BSQ26 arrived from Amazon.

I found myself typically excited when I found the issue in our mailbox. I ripped the package open and took out the hefty tome. Then I opened it to the appropriate page to gaze at my name under the title of my story. I’ve wanted to be a science fiction writer since I was a kid, so this is always the fun part for me.

Only this time it wasn’t so fun.

There, in black and white, wasn’t just my name, but also the name of a close friend, listed as a co-author. A friend who hadn’t collaborated with me on this particular story.

And I realized it was all my fault.

I had started a collaboration with this particular friend, who is also a science fiction author. We didn’t complete the project, but I had made some changes to the configuration of my writing software so it included both our names.

When submitting my story to BSQ, I’d been in a hurry and hadn’t thoroughly checked the exported file. I sent it in with both our names attached.

When the editor sent out the pre-publication proof of issue 26, I didn’t catch the error. At the time, I was under a lot of stress in my day job. I knew I’d proof-read my story pretty thoroughly before submission. I don’t think I opened the proof of the entire volume to double-check. I certainly didn’t catch the error in the author’s name.

I found this to be something of a crushing (and humbling) experience. I had inadvertently used the name of a friend without his permission, attaching it to something to which he didn’t contribute, and with which he might not want to be associated. I’d caused my editor to publish something inaccurate. And I’d created more stress in my life when I already had too much.

All this got me thinking about what science fiction teaches us about making mistakes. Robert A. Heinlein placed into the mouth of his most famous character the cynical view of humans’ capacity to learn cited at the beginning of this article, which doesn’t make me feel great.

But that wasn’t all he had to say on the matter. Elsewhere, he maintains:

“There are three main plots for the human interest story: boy-meets-girl, The Little Tailor, and the man-who-learned-better. Credit the last category to L. Ron Hubbard; I had thought for years that there were but two plots—he pointed out to me the third type.”1

Heinlein further elaborates on the last:

“The man-who-learned-better; just what it sounds like—the story of a man who has one opinion, point of view, or evaluation at the beginning of the story, then acquires a new opinion or evaluation as a result of having his nose rubbed in some harsh facts.”2

A prototypical example of this sort of Heinlein story is his Hugo-winning novel, Double Star, in which the protagonist starts out with a reflexive and unconsidered bigotry toward Martians, only to later be “adopted” into a Martian nest.

If you look at my experience as a very short story, at the beginning I was of the opinion I could juggle a great many tasks and everything would turn out all right. At the end, I realized no matter how much I’ve got going on, I need to take time to check the little things. Otherwise they can turn into big things.

This helps me feel somewhat better. Sure, I screwed up. But I can learn from my mistake, although it may not be either automatic or easy. To really learn from an experience requires time, effort, and commitment. But it’s a great deal better than never learning at all.

Something worth keeping in mind.

Questions or comments? Please share your thoughts!

“On the Writing of Speculative Fiction,” by Robert A. Heinlein, in Turning Points: Essays on the Art of Science Fiction, edited by Damon Knight, ReAnimus Press, 2021; p. 181

“On the Writing of Speculative Fiction,” by Robert A. Heinlein, in Turning Points: Essays on the Art of Science Fiction, edited by Damon Knight, ReAnimus Press, 2021; p. 182

Added footnotes 1 & 2, both citations for the two Heinlein block quotes.